A friend recently asked me when Paolo and I knew we wanted kids, so I tried to remember any big talks we had. I tried and I failed, so I asked Paolo, “Did we ever sit down for a serious discussion around whether we’d have kids?”

“Not that I remember.”

“Me neither! Isn’t that crazy? In a good way, I mean. We were just always on the same page, right? I never questioned it, like going from high school to college. We were doing well with a puppy, and I, for one, raised a thriving Tamagotchi in my youth, so it was the natural progression.”

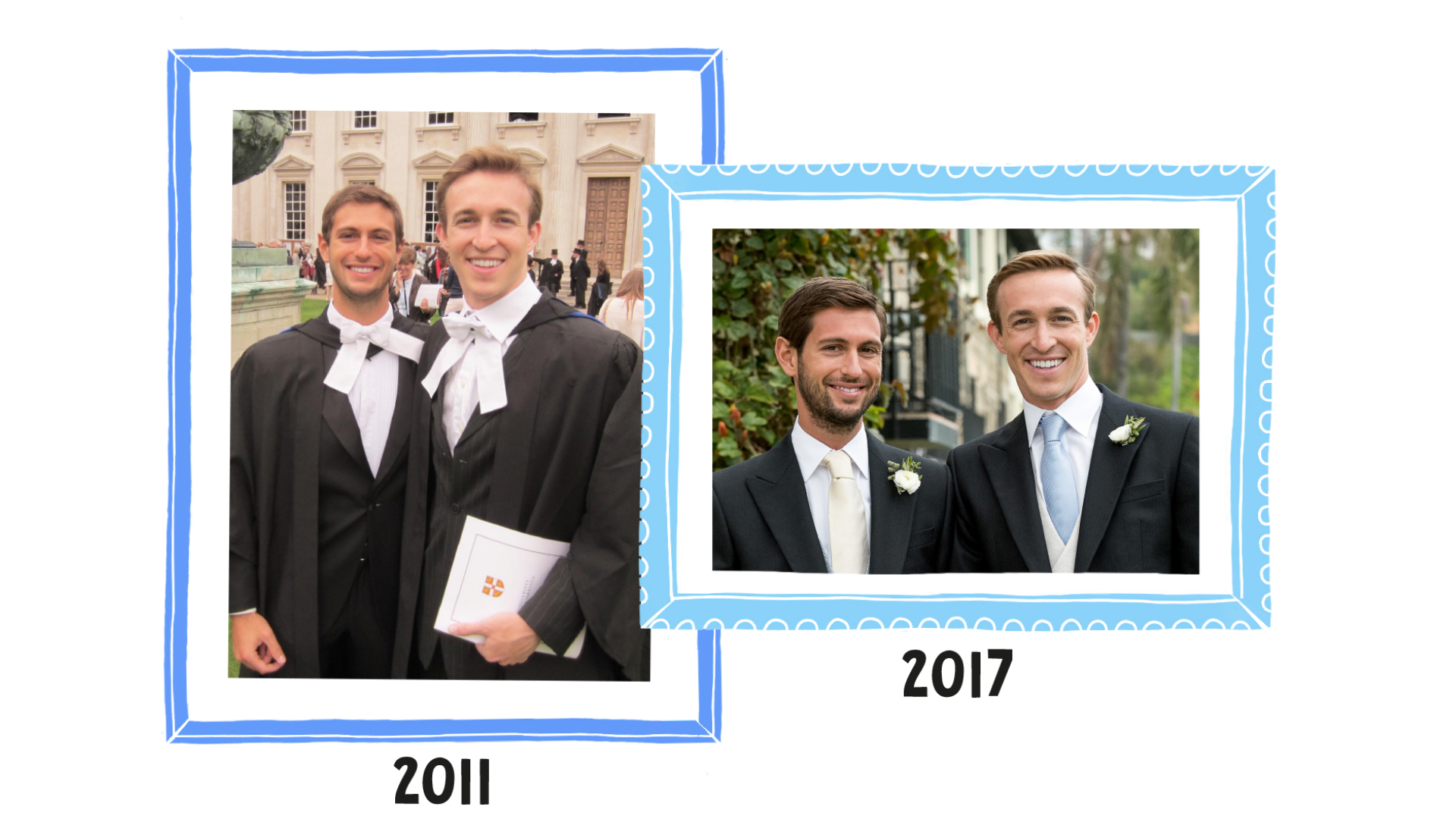

Paolo had stopped listening at this point, but he agreed. When we started dating at 23, whether we’d have kids was not a pressing agenda item. I’d grown up with less lofty aspirations like not getting beat up in a hate crime. As the years went by, it became clear that we both vaguely wanted kids—in that neither of us opposed the notion of fatherhood—and then after we got married, vaguely became concretely.

I’m not sure what I would have done had Paolo felt differently. I wouldn’t have had kids, I suppose. That’s the trippy Sliding Doors truth about much of life: my stance mattered less than happenstance. It was serendipity meeting Paolo in the same master’s program, and I only became dad material due to the sturdy foundation we built over seven years. In a parallel universe where that didn’t happen, I’m a carefree, kid-free gay who never misses a circuit party and only hears the word “Daddy” from twinks in bathhouses.

Back in this universe, we settled down in London and told friends about our plans to pursue surrogacy.

“Surrogacy?” many people asked. “Why not adopt?”

The subtext here—sometimes explicit but more often implicit—was that there were so many unwanted children in the world, so it would be a win-win. It’s a logical utilitarian argument, I’ll give it that, but I resented the knee-jerk reaction to view our family planning as a chance to give back. Friends often assumed we would adopt, and having to correct them made me feel guilty, as if it were selfish to do surrogacy.

Then I’d wonder: was it? Was it selfish to want a genetic link to my children? Was it vain? Or rather: was it more selfish and vain than that same desire shared by heterosexual parents?

In a few instances, I flipped the question around to ask a straight person, “Why didn’t you adopt?” or, “When you’re ready for kids, will you adopt?”

These people laughed uncomfortably like it was an outlandish suggestion or childish retort, then said, as if it were painstakingly obvious, “I can have my own children.”

“We can too.”

“I mean, sure, technically you can,” they’d stumble, “but it’s so much effort and money.”

“Yeah, it’s annoying.”

“Wouldn’t it be easier to adopt?”

Oh, how sweet, you just care about what’s easiest for me.

You see, there’s a fine line between their benign inquiry and a homophobic view that turns “Gay men can’t have their own children” into “Gay men shouldn’t have their own children.” We aren’t meant to be parents, the vitriol goes, and were in fact born this way—with a genetic mutation—to prevent overpopulation. We should quietly enjoy our sodomy and not cheat the system. But if we insist on starting a family, the least we can do is take in an orphan.

I never encountered such brazen antagonism in person, but I sometimes interpreted the “Why not adopt?” question as a watered-down offshoot in suggesting it would be more responsible. Don’t get me wrong, adoption is a wonderful thing, and I have immense respect for parents who do it, but I was against it for two reasons.

(1) On an emotional level, it’s already more complicated for children to have same-sex parents. Adoption, in my opinion, adds another layer

of complexity.

(2) On a practical level, it’s hard for a gay couple to adopt a newborn. Many countries forbid it while others allow it but with red tape like extra background checks to ensure no history of pedophilia. It’s easier to adopt older children, apparently, but that’s not what we wanted. And still, even if an agency claimed to treat all applicants equally, we heard they place gays at the bottom of the pile. No bottoming this time, thank you!